Dairy farming is an around the clock, 365-day-a-year job. At Newmont Farm in Fairlee, Vermont, the Gladstone family milks about 1,400 cows and produces 172,000 pounds of milk daily. Will Gladstone, the farm’s co-owner, says milk production does not dwindle during the winter despite how frigid Vermont can get during those months. In order for this operation to function properly and keep animal comfort at the forefront, winterizing the farm is essential.

In our Q&A with Will Gladstone, he discusses how he and the team handle dropping temperatures without sacrificing productivity at the farm.

Q: When does the winterization process begin at the farm?

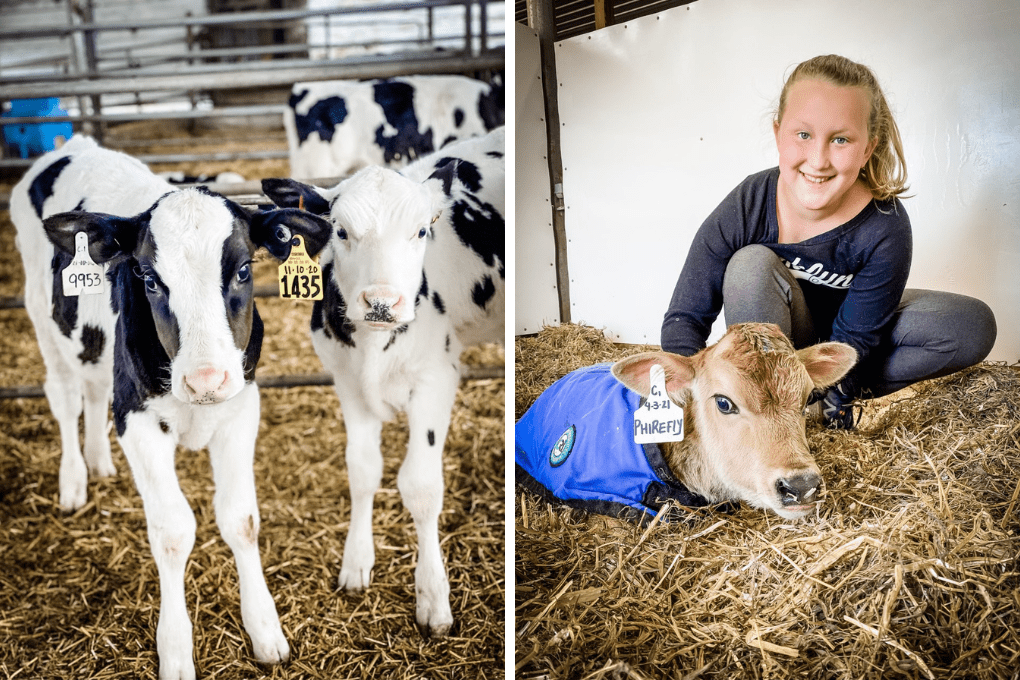

A: It varies based on the size of the animal. For baby calves, we would start bedding them with straw and placing blankets on them around the time it starts getting below freezing at night. That’s likely late October, early November.

Why are you using straw? What’s the benefit of this material?

We’re just doing this primarily with our young stock—calves or heifers. Straw has a better insulation factor based on the fact that it’s hollow and more stemmy. They can nestle into it better than hay or shavings or sawdust. It just keeps them warmer.

How else are you keeping the animals warm?

We also place blankets on the calves and heifers around the time it gets below freezing at night. We have curtains made of vinyl on the sides of the barn. They go up and down the sides of the barn, not on the gable end but on the sides of the building. They open and close based on temperature and are on a thermostat. They would be fully closed [when the temperature reaches] around 35 degrees. On the gable end of the barn, we have doors that we’ll shut when it gets cold, around 40 degrees outside.

When calves are born, we put them in a warm room for about four hours after they’re born, which heats to about 70 degrees to help dry them off. We’ll use bath towels to dry them off, too.

Are there any methods in place for keeping the adult cows warm?

A cow’s thermoneutral zone [a temperature range in which the animals don’t have to expend more energy to maintain a normal body temperature] is between 25 to 60 degrees. If it’s just above freezing in the barn, they’re comfortable.

As far as [drinking] water in the cow barns, there’s enough body heat from the cattle, so it won’t get below freezing. We do have some facilities with younger animals in them [where the water does] get below freezing. We have little electrical heaters that we put into the water to keep it from freezing.

On the equipment side, we’ll plug in and run block heaters on our tractors as needed.

Is there anything in place to prevent the milk from freezing?

No. It’s going through the facility, which never gets below 55 degrees. It’s flowing through a chiller, then filtered, and then goes into a milk tanker. There’s so much insulation in the tanker that the milk [temperature] is probably not changing much more than a degree or so.

The farm’s attention to detail is impressive. It seems as if you get enjoyment out of improving the farm’s operation, no matter the season.

I love the challenge of making our business better all the time and making our farm more productive. I really enjoy improving the business and the diversity of what dairy farming is. It’s not a stagnant, stay-the-same process. There’s always new challenges. And you get to work outside.

For more information about New England dairy farms, visit the “Farm Life” section of the New England Dairy site.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Fred Durso Jr., MS, RDN. Fred was a dietetic intern for New England Dairy at the time this blog was written.