When you drive past a farm field in New England this fall and winter – look closely at what might be growing there. Yes, growing. Farmers are growing plants on farm fields even in the winter. Despite our region’s negative temperatures and snowfalls, farmers have revolutionized sustainable farming in New England and across the U.S. with cover crop and no-till planting practices. New England recorded at least 20% of their available cropland planted to cover crops in 2017. The U.S. average is only 5.6%.

“We have living crops on the fields all year long – what that is doing is capturing sunlight and putting carbon into the soil through living roots,” crop manager, John Hoffman, of Oakridge Dairy in Ellington, Connecticut said.

“We have living crops on the fields all year long – what that is doing is capturing sunlight and putting carbon into the soil through living roots,” crop manager, John Hoffman, of Oakridge Dairy in Ellington, Connecticut said.

Hoffman has been in the business of soil health since 2000 and has his own crop consulting company. Both of his grandfathers were dairy farmers. He calls himself an early adopter of the cover crop and no-till practices that have been rapidly catching on across New England to increase water infiltration and reduce soil erosion.

“Farmers need a lot of support to implement these practices. I became really fascinated with how a farmer was making it work and how he was doing it differently,” Hoffman said.

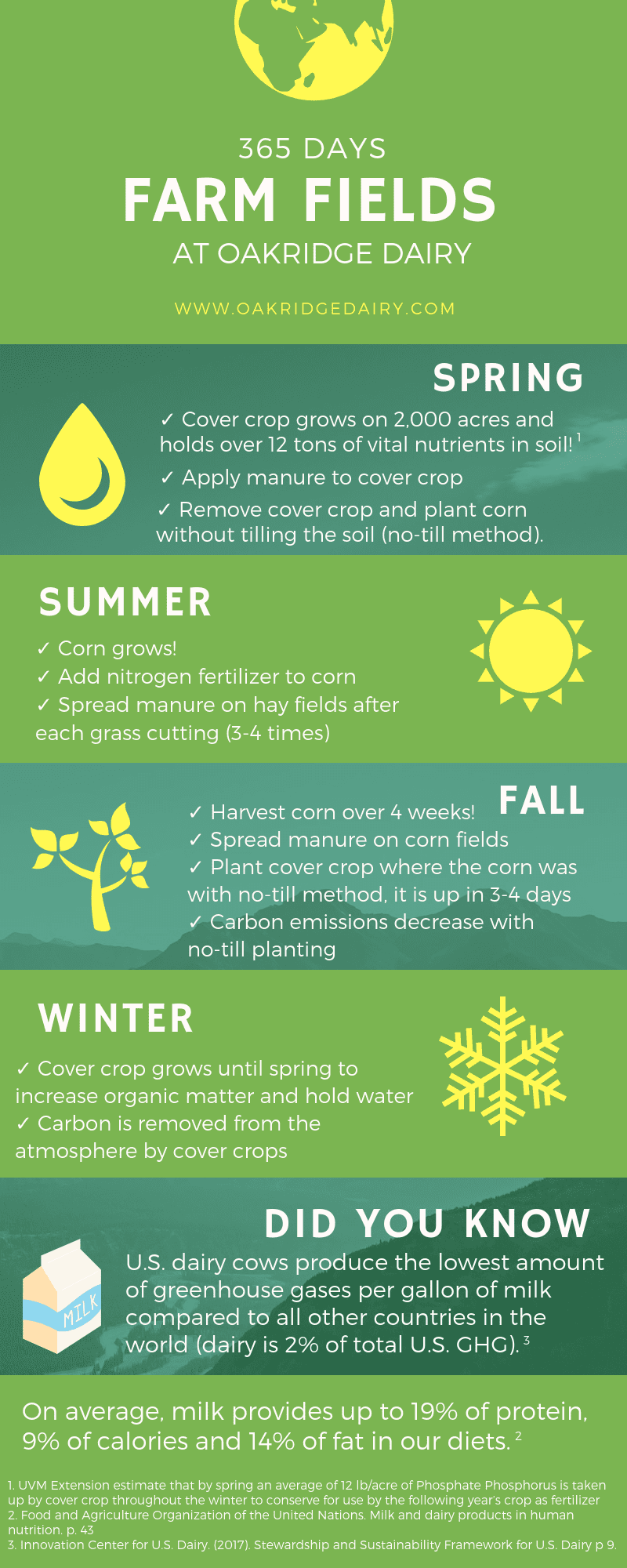

How it Works

In the past after the corn was harvested in the fall, the soil was left bare in the winter and then tilled up in the spring when the corn was planted.

Instead, farmers now plant a second crop in the fall called a cover crop, like winter rye or wheat. It grows through the winter and spring to hold water and nutrients. The cover crop is planted without tilling the soil, using special no-till equipment that penetrates through existing vegetation. In the spring, when it’s time to plant the corn again farmers plant it into the cover crop without tilling the soil. They first terminate the cover crop in an environmentally responsible way either with herbicide, by harvesting it, or by rolling it down flat.

Hoffman says no-till planting has big benefits and has also been shown to decrease carbon emissions compared to conventional tilling.

“If you physically compare land that has not been tilled verses conventionally tilled, it totally changes the biology of the soil – one way is water retention. No-till land is able to pull more water into the soil,” Hoffman said. “Soil that has been tilled soaks in water about an inch and unfortunately the rest of it runs off and takes your top inch of soil with it in the waterways.”’

Technology Improves Corn Harvest

Soil health is also directly related to the nutrient value that will be in the corn that is fed to the cows, and so is the date the corn is harvested. Hoffman has it down to a science, with the help of technology and soil testing.

Corn harvested at Oakridge Dairy in the fall. The cover crop will be immediately planted into the remnants of the corn without tilling the soil.

“We use an app called Encirca. It looks at factors like soil type for every field, weather, soil moisture, and growing degree days which is the number of ideal temperature days for corn growth. It then tells you when the corn will finish growing. We back up 10 days before that to harvest,” Hoffman said.

Soil health and water quality are a big deal when you care for over 2,000 acres of cropland. Oakridge Dairy land spans across the towns of Brockton, Ellington, East Windsor, Enfield, Somers, Stafford, Tolland, Union, and Wales. Hoffman says their goal is to keep the nutrients from manure on the fields to improve soil and water health.

“Many towns in Connecticut no longer have agriculture or open space. People are coming to towns like Ellington, Tolland and Somers where you have open space,” Hoffman said. “Most people that live here long enough expect to smell manure in spring and fall.”

The Role of Manure on the Farm

Oakridge uses manure on their fields that has been separated to have the solids removed. That means their manure is 97% liquid. Recently they’ve been spreading it on more of their fields to help distribute it more evenly.

“It’s important because when we apply manure to a field, it’s equivalent to a quarter inch of rainfall and it soaks right into the soil; there is no caking or a crust layer on the top that you can see,” Hoffman said.

The solid part of the manure is recycled into sterile plant fibers made up of undigested corn and hay. It’s used as bedding for the cows – eliminating the need to import straw or other bedding.

Passion for Protecting the Land

Working the land to make nutritious food is something Hoffman couldn’t imagine his life without. The Agronomy and Crops Team at Oakridge Dairy is the foundation of the farm’s success. Hoffman says the work he does is meaningful because it is a sustainable loop. First, the land is cultivated and crops are grown to feed the cows. Then, the cows make nutritious dairy foods for people. Lastly, the byproduct of cow manure is recycled on the fields to grow more crops in a sustainable cycle.

“I grew up in this town and saw this farm, and I saw an opportunity to do something positive. I went to trade school, but dairy farming was in my blood and there was no getting it out,” Hoffman said.

Learn more about Oakridge Dairy on their website.

Winter rye on a farm field in the spring. Some farmers are experimenting with smashing it down before corn will be planted directly into it.